“I am not at all sure that I know what Americanism really is,” the art critic Elisabeth Luther Cary told readers of The New York Times in 1936, “but so the case stands: Americanism really is, and, in art, Winslow Homer is its great exemplar.” There was little disagreement. His very name seemed made for the job, half muscular Greek adventure, half fretful Yankee Calvinism (his parents were inspired by the Congregational pastor Hubbard Winslow). During his lifetime, he managed—not without strategizing—to be both popular with the hoi polloi and admired by his peers. After his death in 1910, his husky seafarers and oddly concrete ocean sprays were a bridge between old-fashioned storytelling pictures and the 20th-century preference for expressive form. In 1995, when the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C., assembled a magisterial retrospective, Homer was still “America’s greatest and most national painter.” He gave us our best selves: Currier and Ives without the kitsch, modernism with a human face. To John Updike, he was simply “painting’s Melville.”

This kind of flag-waving is no longer fashionable, or even comfortable, in an art world striving to be global and in a country where arguments over what counts as “real America” become nastier by the day. So it is not surprising that “Crosscurrents,” the biggest Homer show in more than a quarter century, positions the artist as part of a transnational Atlantic world, stretching from the Caribbean (where he made radiant watercolors of shark fishermen and limpid inlets) north to Quebec (leaping landlocked salmon and First Nations guides) and east to the English village of Cullercoats (heroic fishwives whipped by wind). In between lie his familiar stomping grounds: the battlefields of Virginia, the rocky coast of New England, the autumnal Adirondacks.

The map thus devised roughly follows the contours of the Gulf Stream, which is also the title of the first Homer painting purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a co-organizer of the exhibition, along with the National Gallery, in London. Indeed, The Gulf Stream (1899) is the centerpiece, a marker for how the curators—Stephanie L. Herdrich and Sylvia Yount in New York, Christopher Riopelle in London—envisage Homer for the 21st century. No longer an oracle of American innocence, he is recast as a poet of observed conflict: North versus South, man versus sea, nature red in tooth and claw.

Painted late in Homer’s life, The Gulf Stream nods back to his earlier dory-in-distress pictures, such as The Fog Warning and Lost on the Grand Banks (both 1885). A sailor is adrift on heavy seas in a boat that has lost rudder and mast, but the setting is not the despondent gray of the North Atlantic—the sea is blue, the sailor is Black, and the home port named on the stern is Key West. Sharks slice through the foreground water, and in place of pallid halibut the deck is strewn with red-and-green sugarcane curled like snakes. In the distance, two possible resolutions to the drama heave into view: on the left, a full-rigged ship and hope of rescue; on the right, a waterspout and certain death. The sailor sees neither—he is looking to the side, beyond the edge of the canvas. We can’t see what he sees, and we have no way of knowing which way the wind blows.

The painting was never universally loved. It took seven years to sell, and was acquired by the Met in 1906 only under pressure from Homer’s peers at the National Academy of Design. Early viewers complained that the boat was too tubby, the drawing inelegant, the story line unpleasant. More recent observers have found the melodrama excessive, like Sharknado without the humor. When it was shown at the Knoedler Gallery in 1902, some female visitors, worried about the sailor’s fate, prompted the gallery to ask for clarification. Homer wrote back:

You ask me for a full description of my picture of the “Gulf Stream.” I regret very much that I have painted a picture that requires any description. The subject of this picture is comprised in its title …

I have crossed the Gulf Stream ten times & I should know something about it. The boat & sharks are outside matters of little consequence. They have been blown out to sea by a hurricane. You can tell these ladies that the unfortunate negro who now is so dazed & parboiled, will be rescued & returned to his friends and home, & ever after live happily.

This testy explanation satisfied no one, and The Gulf Stream has enjoyed a busy life in academic debate ever since, adduced as evidence of the artist’s thoughts on human frailty, Plessy v. Ferguson, the death of his father, or the charm of painterly maritime disasters.

But for more than a century, The Gulf Stream has also been that rarest of things—an acknowledged masterpiece by a beloved artist, hanging in an eminent institution, and featuring a Black hero. It “broke the cotton-patch and back-porch tradition” of representation, Alain Locke wrote in 1935. And if white art historians spent decades tactfully ignoring the implications of skin color, among Black artists The Gulf Stream has been a touchstone. Derek Walcott identifies the sailor with the hero of his epic poem of diasporic Blackness, Omeros. Kerry James Marshall overhauled Homer’s parts to make his own Gulf Stream (2003), in which the water is shark-free, the sloop is yar, and four Black figures relax between the boom and a boom box. Marshall does add a Homer-worthy question mark: the glittery rope that forms the painting’s ornamental surround is broken on one side—an emblem of emancipation, perhaps, or of a doomed ship.

The Homer of The Gulf Stream is both more worldly and more elusive than the Homer of little red schoolhouses and sou’westers. And what the 90 or so paintings and watercolors assembled in “Crosscurrents” make clear is that the most salient quality of his art was never straightforwardness; it is his knack for using visual precision to demonstrate the limits of vision. We can see what is happening but not what will happen. He is the master of the ambiguous outcome, which also makes him the master of the unclear moral: Believe in the ship, and The Gulf Stream is a lesson in forbearance; believe in the waterspout, and it is a lesson in futility.

The opening of “Crosscurrents” coincides with the publication of a new biography, Winslow Homer: American Passage, by William R. Cross. Both endeavors aim to refresh our understanding of an artist already familiar to most museumgoers, and both face the same hazard—a mulishly unwilling subject. Not for nothing was Homer known as the “Obtuse Bard” in the annals of one of the artists’ clubs he belonged to. His letters could be chatty about fly-fishing, but were circumspect to the point of muteness on questions of love and art. How do you re-create the inner life of an artist who did not talk about art?

Homer’s outer life is known well enough. Born in Boston in 1836 to an old and intermittently prosperous Yankee family, he was apprenticed to a lithographer before setting out on his own as a freelance illustrator. By 1859 he was in New York City, supplying the new mass-market periodicals like Harper’s Weekly with frothy scenes of dancing cadets and ladies riding sidesaddle. If his anatomy was a bit Gumbyish and his faces were little more than masks, his drawings had enough panache to survive the ossifying translation into wood engraving. When Harper’s sent him to Virginia to cover the Civil War, he found his forte in closely observing camp life, attending to “the ordinary foot soldier,” Cross notes, “not the general.”

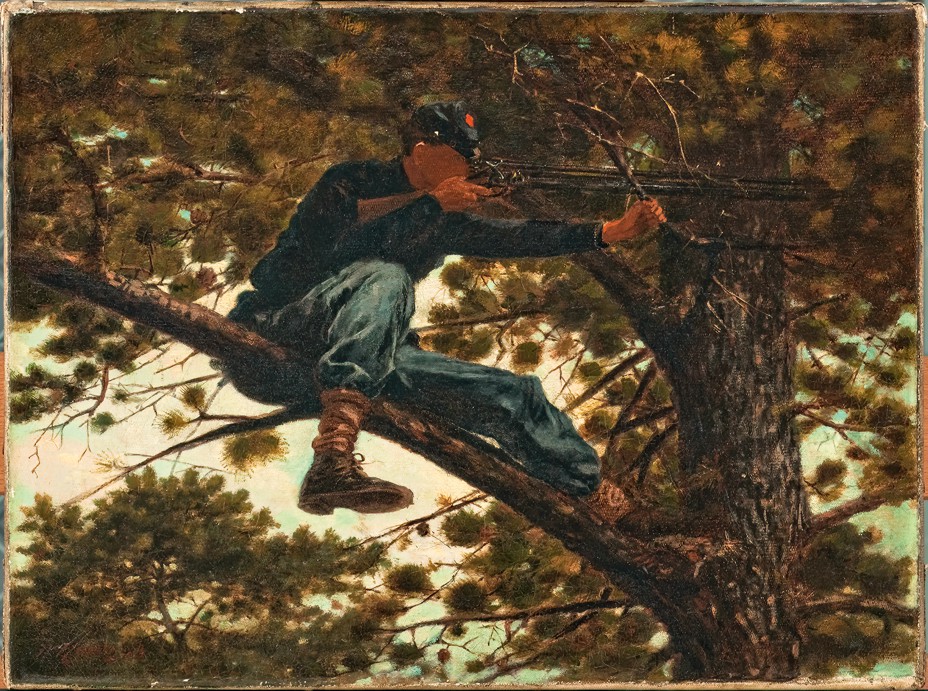

Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910). Sharpshooter, 1863. Oil on canvas. 12 1/4 x 16 1/2 in. (31.1 x 41.9 cm). Portland Museum of Art, Maine, Gift of Barbro and Bernard Osher (1992.41). Photo courtesy of Meyersphoto.com.

He had ambitions. In New York he attended life-drawing classes and received basic painting instruction. He studied how-to books and prints of European paintings. He learned to set people, places, and things on geometric scaffolds, giving the most happenstance of subjects a sense of sublime order. (A beautiful 1877 watercolor of a young woman pointing out geometric figures on a blackboard feels unexpectedly personal, with his signature placed as if chalked on the slate.) Not a natural when it came to color, he relied heavily on Michel-Eugène Chevreul’s 1839 book, The Laws of Contrast of Colour. Like artists his age on both sides of the Atlantic, he borrowed spatial ideas from Japanese woodblocks, and was alert to the look of photography (he redrew Mathew Brady photographs for Harper’s, and owned cameras himself).

The wood engraving of a Union sharpshooter perched in a tree that appeared in the November 15, 1862, issue of Harper’s bore a new credit line: “From a Painting by W. Homer, Esq.” The topic was newsworthy for a magazine—equipped with telescopic sights, sharpshooters represented a novel type of warfare, capable of hitting a target hundreds of yards away from a concealed position—but it was a peculiar subject for a painting. War paintings were generally stagey battle scenes. Sharpshooter is more like a genre painting of a man at work; his work just happens to be killing. Years later, Homer wrote that the scene was “as near murder as anything I ever could think of in connection with the army.” Sharpshooter is taut with anticipation—the tensile crisscross of rifle, branches, and human limbs is worthy of Franz Kline—but it is impossible to say if it shows a hero or a villain.

Prisoners From the Front (1866), a record of the Civil War acclaimed for its social allegory, made Homer’s reputation as a serious artist. There was the northerner exuding “the dignity of a life animated by principle,” his friend Eugene Benson wrote in the New York Evening Post, facing the “audacious, reckless, impudent young Virginian,” the “bewildered old man, perhaps a spy, with his furtive look,” and “ ‘the poor white,’ stupid, stolid, helpless.” Easy-to-read typologies were part of his illustrator tool kit, but here they acquired a restrained gravitas.

When the picture was exhibited at the 1867 Exposition Universelle, in Paris, Homer made his first trip to Europe. He landed in Liverpool and may, as Cross suggests, have lingered in London, taking in the bounty of Turners and the Raphael Cartoons. Or maybe not. Neither there nor in France did he leave a record of what he saw or what he thought about it.

In New York he was evidently clubbable, elected to the Century Association and the National Academy of Design—then the city’s premier exhibition venues—while still in his 20s. In the summers he headed to the country with friends: the White Mountains, the Hudson River Valley, the Adirondacks. He painted people at play (the small and wonderful croquet paintings of 1866), but more often he painted them at work out of doors. He also traveled to the former Confederacy, painting scenes of African American life.

Critics often took Homer to task for his abrupt color and rough paint, which tugged at the edges of attention, spoiling the illusion. His working-class subjects were found uncouth, his depiction of a Black family’s dovecote “slovenly.” And yet his pictures rewarded the eye in ways that flummoxed the most sophisticated of onlookers. Henry James, who would have preferred scenes of Capri, wrote that though Homer chose “the least pictorial range of scenery and civilization; he has resolutely treated them as if they were pictorial … and, to reward his audacity, he has incontestably succeeded … Our only complaint with it is that it is damnably ugly!”

Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910). Snap the Whip, 1872. Oil on canvas 12 x 20 in. (30.5 x 50.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Christian A. Zabriskie, 1950 (50.41). Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

What redeemed him was attentiveness. Even when the subject is banal, his line is unexpected, diverted from cliché by incident—the peculiar crumpling of a sail, or the irregular break of a ripple. Each object has a specific weight, as well as a sense of incipient motion; it feels as though everything is about to come apart. His famous scene of barefoot boys playing, Snap the Whip (1872), is unusual in showing the moment after the break, rather than the moment before.

These qualities erupted with fresh clarity when he turned to watercolor in 1873. The first picture he ever exhibited in New York had been a watercolor, but the medium was still disdained for its association with female amateurs (including Homer’s mother, an accomplished flower painter). So he mastered oil painting, but his oils somehow always feel like work in a way the agile, brilliant watercolors do not. In watercolor, the fall of light on a child’s bare back evokes an event rather than an effect.

Returning to England in 1881, Homer settled in Cullercoats, a fishing port with bad weather where artists specializing in the “peril at sea” genre gathered. Working mainly on paper, he stripped back and decluttered his compositions, endowing his fisherfolk with caryatid majesty.

It was also in watercolor that he recorded the leaping light of the Caribbean. Once treated as a sidenote, the Caribbean watercolors constitute roughly a third of the works in “Crosscurrents.” This emphasis is a corrective for past omissions, and builds a visual and conceptual context for The Gulf Stream. (Also, they are simply beautiful.)

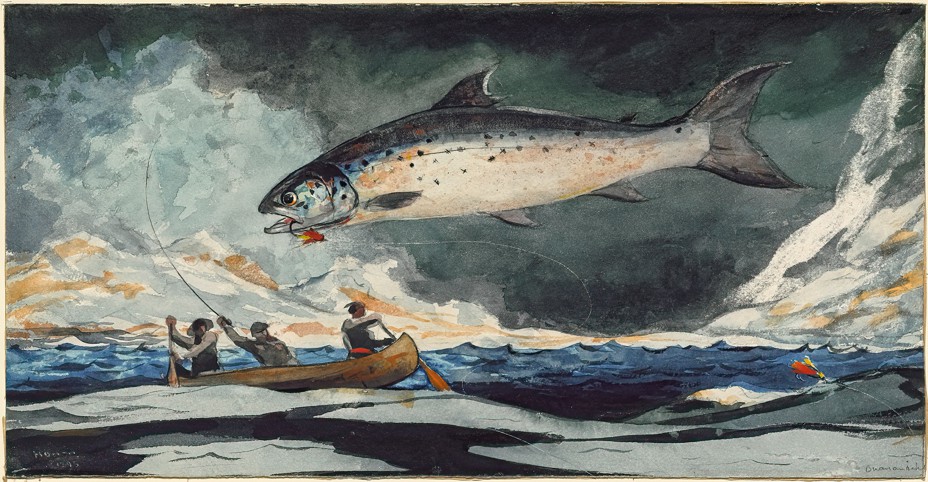

The last third of his life was spent mostly in Prouts Neck, a slip of land on the coast of Maine where his family had acquired property. He continued to travel—willingly for fishing, less willingly for the various honors that came his way. Curiously, for all his love of wilderness, he never went farther west than Chicago. “While his compatriots were chasing Native Americans across the plains of South Dakota,” Daniel Immerwahr writes in the catalog for “Crosscurrents,” “Homer was painting bucolic watercolors of dogs, deer, and trout in the Adirondacks.” The pictures were not always so bucolic (especially for the deer), but they made nature present, not as an awe-inspiring panorama in the manner of Frederic Edwin Church or Albert Bierstadt, but as an intimate encounter. In the extraordinary watercolor A Good Pool, Saguenay River (1895), a huge salmon hangs in midair above the choppy waters, while from a canoe below, a hairline filament loops through the air like a pen flourish, ending in the red fly that has just caught the fish’s cheek. Everything is connected.

Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910). A Good Pool, Saguenay River, 1895. Watercolor and graphite on wove paper. 9 3/4 x 18 7/8 in. (24.7 x 47.9 cm). The Clark Art Institute. Image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute, clarkart.edu.

It was at Prouts Neck that Homer painted the late, great meetings of sea and shore that kept his reputation alive among modernists made itchy by narrative. In these, he made literal the rhetoric in his sassy note about The Gulf Stream: Boats and fish and all “outside matters” have been dismissed, leaving light, and weather, and tides—motion without human motivation, time without end.

In the midst of listing all the things he detested about Homer’s art, Henry James paused to admit: “There is nevertheless something one likes about him.” For a century and a half, people have been explaining that liking in different ways. Homer’s vaunted Americanism was one. In this line, he was celebrated as an autodidact, free of inherited airs or any “hint of Europe or of Asia.” Helped along by his reticence to wax lyrical in writing, his “down-to-earth honesty” devolved into a kind of wholesome stupidity. As the National Gallery of Art curator Nicolai Cikovsky put it in 1995, “It has not been customary to regard Homer’s intellectual and moral equipment as significant aspects of his artistic enterprise.” Earlier writers topped off their portrayals with an almost parodic masculinity: His style was “manly,” his subjects were “virile,” and even the effeminate watercolor was, in his hands, “pre-eminently a man’s art.” About this diffident and reportedly dapper man, his first biographer enthused, “Like the men of Viking blood, he rises to his best estate in the stress of the hurricane.”

This Thor–meets–L. L. Bean character bears little resemblance to the sophisticated and strategic, if enigmatic, Homer presented in the new biography and the “Crosscurrents” catalog essays. The authors emphasize virtues likely to appeal to us now: his interest in depicting Black people, working (not just ornamental) women, and environmental systems. In keeping with today’s scholarship, the catalog considers the exhibit’s artworks as vectors of social and political forces. Immerwahr examines Homer in light of America’s territorial and economic expansion, asking whether the entrancing Bahamian watercolors might be “an invitation to empire”; Gwendolyn Dubois Shaw digs into Homer’s difficulties aligning observation with received wisdom in his depictions of Black Americans; Stephanie Herdrich uses The Gulf Stream as a jumping-off point to explore conflict and mortality in Homer’s career; Sylvia Yount maps a mountain of Homer scholarship; and Christopher Riopelle surveys Homer’s relationship to Europe.

Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910). The Turtle Pound, 1898. Watercolor over pencil, 14 15/16 x 21 3/8 in. (38.0 x 54.2 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Sustaining Membership Fund, Alfred T. White Memorial Fund, and A. Augustus Healy Fund (23.98). Photo courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

Cross’s book, by contrast, is a hefty, traditional “life of.” Not particularly interested in investigating systemic power and privilege, Cross draws out aspects of life that may have figured more consciously in Homer’s own mind, acknowledging without contempt, for instance, Homer’s pragmatic approach to business. Summers in the country may have offered “solace … after the trauma of wartime,” as Herdrich writes, but they were also a way to stockpile sketches of the kind of sunlit scenes collectors liked to buy. When paintings didn’t sell, he kept fiddling with them, whether for his own enjoyment or to second-guess the market, and he was not above painting the same picture twice (there are two versions of Snap the Whip, one with eight children, one with nine). “I will paint for money at any time. Any subject, any size,” he told a dealer in the 1890s.

Cross also gives substantial space to religion—both the theological debates over slavery that roiled New England during Homer’s childhood and the later proliferation of natural theology, the belief that divine order was revealed through the natural world, which underlay many of the books, both scientific and spiritual, in Homer’s library. If he can be seen as a proto-feminist and proto-environmentalist, his reasons were different from our own.

There are still huge holes, including the nature, or even existence, of Homer’s love life. Was his heart broken by the artist Helena de Kay (of whom he painted a rare portrait in a Whistlerish mode)? Or by the businessman Albert Warren Kelsey (with whom he posed for a chummy photograph in Paris)? Cross alerts us to the theories, but warns that there are only “a few shreds of evidence” of any specific sexual dalliance. And while it is hard to disagree with Herdrich’s observation that Homer seemed “to revel in depicting healthy, young, Black bodies glistening in warm water and sunlight,” the same might be said of his attitude toward fish.

Art-historical queries run into similar dead ends. Homer was in Paris at a crucial moment in the history of Impressionism, but the all-important issue—what did he see and when did he see it?—subsides into speculation: “Surely,” writes Riopelle in the “Crosscurrents” catalog, “Homer rushed to Manet’s pavilion.” “One cannot imagine that he would have missed it,” Cross concurs. The tale chugs along on a track of “would haves” and “must haves.”

“The most interesting part of my life,” Homer wrote when refusing to assist an aspiring biographer, “is of no concern to the public.” That statement is extraordinary—an overt tease (what is the most interesting part?) followed by a slammed door. It feels curiously familiar. That push and pull, like the alternation of clarity and opacity in his biography, also haunts his pictures.

Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910). After the Hurricane, Bahamas, 1899. Watercolor and graphite on wove paper. 14 5/8 x 21 3/8 in. (37.2 x 54.2 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection (1933.1235). Image courtesy OF The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, N.Y.

The shyness of Homer’s people has often been remarked on. They turn their back, look over their shoulder, veil their features with slouchy hats and falling hair. It has been suggested that he was just bad at faces, but he could paint them with grace when he wanted to. The habit is too persistent not to be purposeful, and it has a distinct effect: Instead of looking at people, we end up looking at people looking at things we cannot see. Soldiers look through rifle sights; sailors look to sea. Wading children bend over to look under the water’s surface. Sometimes, as in the poignant Waiting for Dad (Longing) (1873), we have a clue about what they are looking for, though not what they actually see. In Two Guides (1877), a gray-bearded mountain man (he could be a model for Gabby Johnson, the speaker of “authentic frontier gibberish” in Blazing Saddles) extends his arm and index finger to point at … something.

It is perennially surprising, when you come across Homer paintings on a museum wall, to discover how small they are, mostly in the two-by-three-foot range. (Kerry James Marshall’s Gulf Stream occupies 12 times the area of Homer’s.) This domesticated scale, however, was “not calculated for the drawing-room,” his friend Kenyon Cox wrote, but for grander, more spacious venues. Homer wanted people to “stand off,” and derided the habit of leaning in as “smelling” a picture. He once asked that a painting be hung in a gallery window so it could be seen “properly from the opposite side of 5th Ave … as it is painted at the distance of 60 feet.” In Prouts Neck, he explained, “I hang my pictures on the upper balcony of the studio, and go down by the sea seventy-five feet away, and look at them.” Embedded in the shadow of a wave, beneath his signature on The Gulf Stream, is the painted message “At 12 feet from the picture you can see it.”

From that distance, Homer’s famous brusqueness is smoothed out and the illusion of space deepens. He explained that the “first shark” was 15 feet long and 30 feet forward of the boat. But if you stand just two feet away, it looks like the sailor could reach out and pet it. Only from a distance does the space stretch out. Up close you might see how the trick was played, but you lose the magic.

Homer may indeed be painting’s Melville, not because of the passport he held, but because he could cram so much precision and perplexity into a single breath.

This article appears in the May 2022 print edition with the headline “Winslow Homer’s America.”

* Lead image: Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910). The Gulf Stream, 1899. Oil on canvas. 28 1/8 x 49 1/8 in. (71.4 x 124.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1906 (06.1234). Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.